Ivan De Luce || November 6, 2023

Have you ever wondered why journalists use phrases like “burying the lead” or terms like “nut graph,” or why these words are sometimes spelled “lede” and “nut graf”?

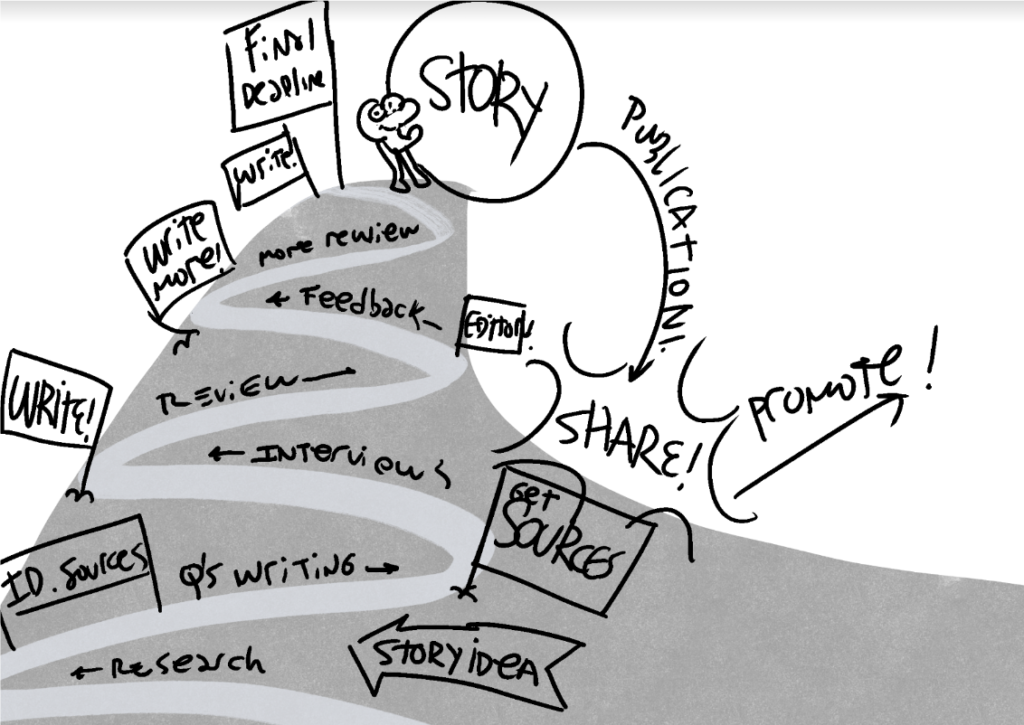

To answer these questions and many more at the heart of what makes a great news story, The Kiosk held the second workshop in its Fall 2023 Journalism Workshop Series. The workshop, which focused mainly on the anatomy of a news story and identifying sources, was offered on October 24 virtually via Zoom.

The workshop was hosted by Katina Paron, who serves as the editor of Dateline: CUNY. Paron has spent years as a journalism educator, and has also authored the book “A NewsHound’s Guide to Student Journalism,” an indispensable introduction to writing for school newspapers.

To kick off the workshop, Paron focused on the anatomy of a news story, or all the parts that come together to create what readers expect from a story. To start most stories, reporters need a “lead” (also spelled as “lede” to not get it confused with the correctly spelled words of a story draft). The lead is the first sentence that draws the reader in.

“A lead is a flashlight that you shine into the well of the story,” Paron explained by way of paraphrasing writer John McPhee. “You don’t have to see all the way to the bottom. Just far enough to know what you’re getting into.”

The lead can come in many forms. Here are a few that Paron mentioned:

- News/summary: Breaking news stories tend to start with these leads, which get straight to the point and explain what happened up front.

- Anecdotal: This slower, more descriptive lead starts the story with a small anecdote to illustrate a larger point.

- List: These leads draw the reader in with a list of things pertaining to the story.

- Startling statement: Sometimes, shocking the reader with a crucial fact or detail will keep them reading, but it’s important to avoid clickbait-like tactics.

- Wordplay: If the headline wasn’t enough of a chance to get punny, the lead might be a good chance to elicit a chuckle from the reader.

The story you’re reading, for example, uses a mix of the list and anecdotal leads and asks a question or two to draw the reader in.

Paron also quoted from one of the best writing handbooks a reporter can buy, “On Writing Well” by William Zinsser: “The most important sentence in any article is the first one. If it doesn’t induce the reader to proceed to the second sentence, your article is dead.”

After the lead comes the “nut graph,” a paragraph that sums up the story in a nutshell, usually right after the lead, Paron explained. Breaking news stories sometimes skip leads altogether and go straight into the nut graph.

The nut graph “summarizes the results of your reporting,” Paron said. “It’s the ‘what was, what’s new and what’s now.’ So what was happening? What’s new and why does it matter? What’s happening now?”

After the lead and the nut graph, quotes are the third crucial element of a story. The key to getting good quotes begins with finding the right sources, Paron said.

“We don’t know the answers, but we are in charge of finding out the answers,” she said. “We don’t need to know the information, but we need to find the right people with that information.”

In fact, sources, a combination of interviews and research, are so important that they take up 95% of most stories, Paron added. To find the right people, reach out to who is directly involved in the story, who might be directly impacted by it, who made the decision for the story to happen, and who has personal or professional experience on the topic.

“Experts can be anything,” Paron said. “I love to say, especially about young people and about students, that students are the experts of their own experiences.”

Paron’s workshop covered much more than the points mentioned here, but this should serve as a useful starting point for any aspiring journalist. If you’d like to pitch to The Kiosk, check out our submission guidelines.

The Kiosk will be holding one more workshop this semester, on Tuesday, November 14. Please join us!