Writing Against the Clock

I sit beside my abuela in hospice, notebook in hand, trying to capture the cadence of her voice as the nurse quietly adjusts her IV. The machines hum, indifferent to memory, but Abuela’s words cut through. She’s retelling her role in the Grito de Jayuya of 1950: smuggling messages under the noses of colonial authorities, organizing with other women, and dodging surveillance. Her story pulses with urgency, and I feel the weight of history pressing against the sterile present.

Outside, the world churns. Puerto Rico faces another wave of protests, this time over energy privatization, colonial debt restructuring, and the lingering shadow of U.S. oversight. Students march, elders chant, and the streets echo with demands for autonomy. I scroll through headlines between Abuela’s pauses, watching history repeat in real time. Her revolution isn’t just memory, it’s a blueprint.

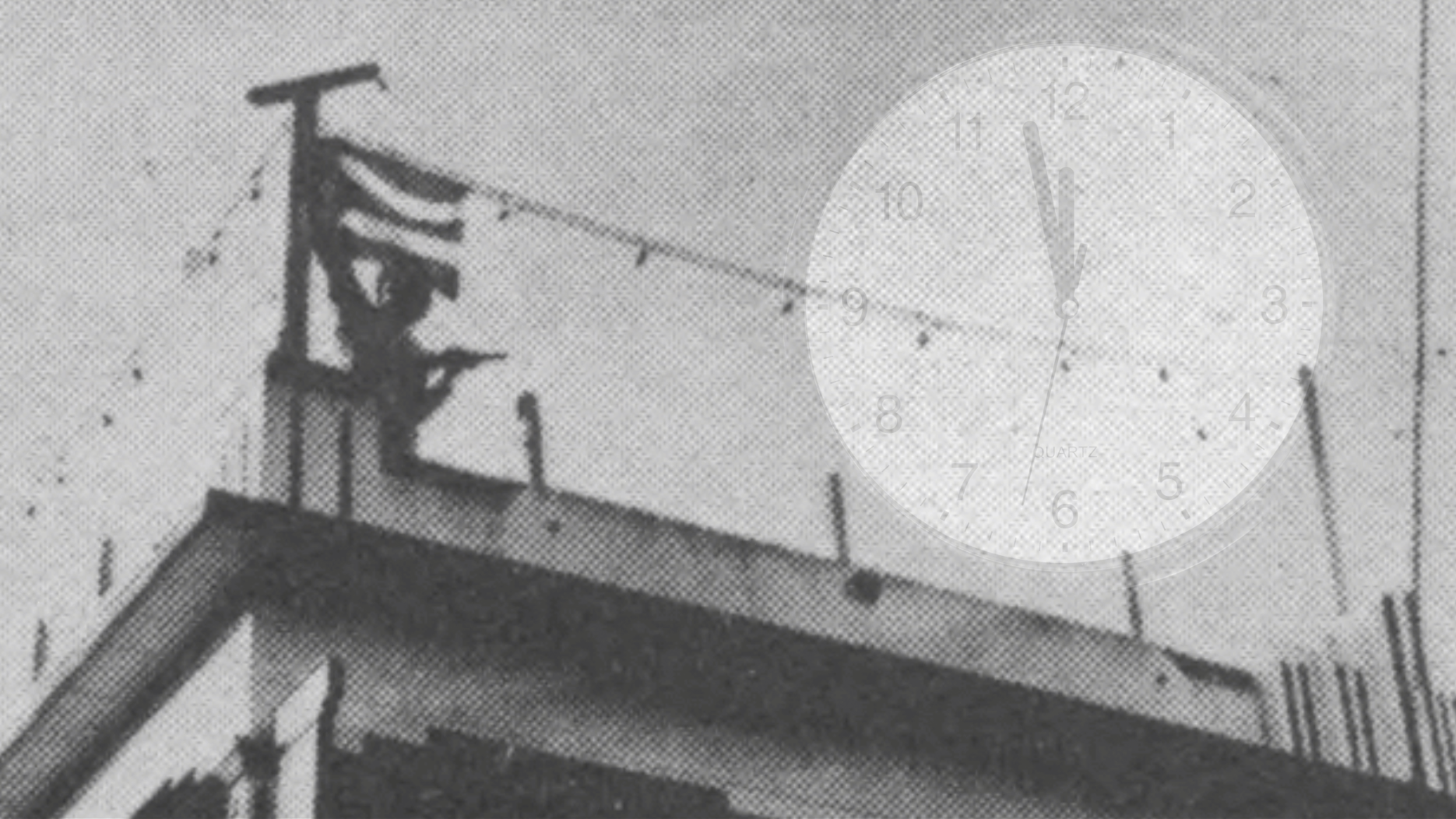

David Harvey’s The Condition of Postmodernity describes modernity as “time-space compression,” where technological advances shrink distances and accelerate life. Abuela’s resistance unfolded in a Puerto Rico already shaped by these forces: telegraphs, radios, and overhead planes dictated the tempo of defiance. Today, it’s hashtags, livestreams, and drone footage. The rhythm of resistance, however, remains unchanged.

Stephen Kern’s The Culture of Time and Space explores how modernity fractured our experience of time, replacing organic rhythms with mechanical precision. I see this in Abuela’s recollections. Her story isn’t linear, but a mosaic of urgency, fear, and defiance. Her resistance defied the clock. So do today’s protesters who disrupt schedules, reroute traffic, and reclaim time as a tool of resistance.

Her memories don’t follow a timeline. They leap from hiding in a church basement to hearing coded messages on the radio . . . from the scent of coffee to the sound of boots on gravel. She speaks in pulses, not paragraphs. I write in fragments trying to honor that rhythm.

As I scribble, I’m haunted by Chaplin’s Modern Times where the worker is consumed by the machine. I, too, feel that pressure: algorithms, deadlines, the constant churn of content. But Abuela’s story reminds me that writing can be resistance. Her voice, even now, disrupts the sterile hum of modern life. In her memory, I find a counter-narrative to the mechanized present–a reminder that time is not just measured by clocks, but by courage.

Modernity demands speed, clarity, and productivity. Abuela’s story resists that. It’s messy, nonlinear, and full of pauses and tangents. She interrupts herself to ask about my classes, to complain about the soup, to laugh at a memory only she can see. And I realize: this is the rhythm I want to write in. Not the rhythm of the machine, but the rhythm of memory.

Her voice slows. She tells me about the women who sewed messages into hems, and passed notes in loaves of bread. She names them: Isabelita, Marta, Doña Luz. I write each name carefully, as if inscribing a monument. Isabelita refers to Isabel Rosado, a lifelong independence activist and Nationalist Party member who was imprisoned after the 1950 uprising. Marta and Doña Luz may not appear in official records, but they represent the countless women whose heroism lives in family memories and community whispers. These women weren’t just resisting colonial rule. They were resisting erasure. And now, so am I.

I look at my notebook. It’s messy, full of arrows and cross-outs. But it’s alive. It holds a rhythm no algorithm can replicate. I think about Harvey again, how modernity compresses time and flattens space. Abuela’s story, by contrast, expands time. It stretches across generations, across languages, and across the sterile hum of machines.

When I leave the hospice, I feel disoriented. The world outside is fast: cars, screens, notifications. But I carry Abuela’s rhythm with me. I write not to keep up with modernity, but to reclaim the stories it tries to erase. I write to honor the pauses, the tangents, and the fragments. I write against the clock.